Aug 25 2014

Wes Welker Concussion – Is this the One that Forces Retirement?

Wes Welker Concussion – How Many More Can He Absorb?

By Gordon Johnson

Broncos’ wide receiver Wes Welker suffered another concussion on Saturday night. It was his third in 10 months. I am not a doctor and certainly not Wes Welker’s advisor. Yet as Welker is only one of thousands of athletes who must make the choice as to whether to continue to play despite the risk of permanent deficits from concussion, I think it is worthwhile to itemize some of the factors that should be considered in such a situation.

Concussion is a form of brain injury that usually does not disable, from which there is an “apparent full recovery” as much as 90% of the time. But not everybody has a favorable recovery. Before a player makes the potentially life altering decision to expose himself to another concussion, I think it is imperative that he hears an outside voice about the risk factors.

I had been struggling with understanding why some people, including myself, had relatively good recoveries from even significant brain injury when others did so badly afterwards. Then I grasped the key:

Concussion is a sufficiently mild form of brain injury that only the most vulnerable people are likely to be disabled by it. If you have a disability as a result of a concussion, the likely reason is that the injured person has a pre-morbid (pre-injury) vulnerability to that disability.

What are the vulnerabilities? The risk factors for a bad result are primarily the following:

- Concussion History

- Headache History

- Developmental History

- Psychiatric/Anxiety History

- Age (approaching 40).

Even the most conservative brain injury expert will not dispute those risk factors. While there is an entire group of researchers who stubbornly claim that a “single uncomplicated mild traumatic brain injury” does not cause any permanent brain damage, inherent in that claim is the admission that the “second” MTBI might. Of course if the first concussion didn’t cause any permanent brain damage, the occurence of the second concussion wouldn’t make any difference.

What we don’t know is how many concussions are too many. Such a determination is extremely difficult to make because we never know how serious any given concussion is or how vulnerable a given brain. But before making the return to play determination it is imperative to know as much as possible.

Beyond Neuropsychological Testing. Traditionally, the inquiry as to how much damage a given concussion leaves is in the province of the neuropsychologist. But the problem with relying on a neuropsychological inquiry (as the NFL concussion settlement does) is that neuropsychology testing only illuminates the cognitive element of the brain damage equation. That equation also includes behavioral, mood and physical manifestations. Without consideration of the other three domains of traumatic brain damage, one cannot fully assess the risk factors of further exposure to concussion risk.

Mood isn’t hard to see if the diagnositician opens his or her eyes to it. Although behavior abnormalities are difficult to measure, they fit into recognizable patterns and are not hard to spot if one investigates the injured person’s behavior outside of the doctor’s office. However, it is necessary to talk to someone other than the injured person to get a sense of that. Collateral interviews of friends, family members and co-workers are critical. Neurological and physical deficits can often be measured with the right tests.

Modern MRI can Help. Clearly, if there is identifiable brain damage, the player should retire from football. Yet after concussion, that damage is often difficult to see in imaging studies. Traditionally, little could be told about brain damage after concussion by imaging studies such as MRI and CT scans. Concussion injury is often limited to diffuse axonal injury and axons are too small to be seen on MRI. See https://braininjuryhelp.com/post-concussion-neuroimaging-advances/

However, modern neuroimaging now includes such techniques as Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) and brain volume studies. The important study done by Marchi, et. al. at the Cleveland Clinic and Rochester University found abnormalities on DTI even in football players who had significant sub-concussive blows. (Subconcussive meaning less than sufficient to cause independent concussions.) Thus, if you are an athlete doing due diligence on your own brain, have DTI imaging done. For Marchi study, click here: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0056805

However, modern neuroimaging now includes such techniques as Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) and brain volume studies. The important study done by Marchi, et. al. at the Cleveland Clinic and Rochester University found abnormalities on DTI even in football players who had significant sub-concussive blows. (Subconcussive meaning less than sufficient to cause independent concussions.) Thus, if you are an athlete doing due diligence on your own brain, have DTI imaging done. For Marchi study, click here: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0056805

Brain volume studies indicate whether brain damage has resulted in the shrinkage in the size of the brain and/or substructures of the brain. Damage to important structures like the hippocampus (the brain’s save button) can now be measured. If the hippocampus is shrinking, might be a good time to stop playing.

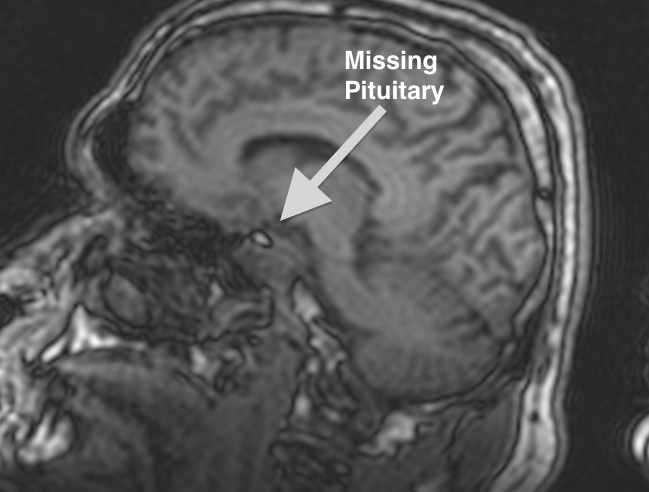

Another area which can be measured today is abnormal hormonal levels. Long term exposure to concussion can result in damage to the bodies hormonal system (endocrine system), particularly to structures such as the pituitary gland. MRI may show atrophy there and hormonal tests can also indicate pathology.

The lighter spot in the center of this image is a cavity where the pituitary gland is supposed to be. Most of this pituitary gland was lost as a result of a mild traumatic brain injury.

The other approach to making return versus retire decisions, is to think of the decision in terms of reserves. Our brain’s are believed to develop with certain reserve capacity. Some of that reserve capacity is lost as we age. More is lost by traumatic events, disease, heart problems, drugs or alcohol use. Under this theory, if the amount of the loss of reserves is above the line, then perhaps there will be no disability. If the amount of reserves goes below the line, then disability will begin to show up. Think of it like you might the 53 man roster in football. A team can play with 50 players, but if the loss drops to something below 40, it might become challenging to field a team. If like the brain, there is no way to add or sign new players, if you keep having injuries, at some point there are not enough players to compete.

Demonstrated here is the concept of decreasing capacity to absorb neuron loss as an individual ages.

Age. As shown here, the older a person, the fewer reserves available. But age is more than just a matter of diminishing reserves. Age is also important because as a person approaches the age of 40, the ability of the brain to recover through a process called neuroplasticity is diminished. It is believed that neuroplasticity is closing connected to the growth hormone in the brain. The brain’s production of growth hormone drops off dramatically at age 40. The closer an athlete is to 40 when injured, the less likelihood that the brain can recover from the effects of a concussion.

No athlete wants to ever admit his or her vulnerability. No athlete wants to be forced to retire, or even miss a substantial period of time due to a concussion. Yet, while an athletic person may recover quickly from the first concussion, each successive concussion likely makes the recovery more complicated, and the potential for long term deficits more likely. While we cannot eliminate the risks of concussion in football, we can limit the disability resulting therefrom if we make sure the vulnerable minds don’t continue to be exposed.